Fifty-two discoveries from the BiblioPhilly project, No. 6/52

Georges Chastellain, c. 1402/1410–1475, L’outré d’amour pour amour morte, Philadelphia, The Rosenbach Museum and Library, MS 443/21, fol. 1r, with miniature showing The author dreaming

While being attentive to the circumstances surrounding the genesis and production of a Medieval or Renaissance manuscript is often our primary concern as scholars, sometimes the subsequent destiny of an item can be equally engaging, if not more so! This is especially the case when the attested later owner of the book is A) relatively close in date to the production of the manuscript and thus valuable as a witness to the early diffusion of a particular text, and B) known to have owned other books and documented for having had a particular focus to their bibliophilism. Today we will examine a manuscript which, though notable for its textual content and illustrations, is of further interest due to its rich early ownership history, which has never before been remarked upon.

This short, rhymed work in French by the Burgundian chronicler and poet Georges Chastellain (c. 1402/1410–1475) is entitled L’outré d’amour pour amour morte, which can be rendered in English as something resembling “The Lover’s Lament over the Death of his Love” (see here for the digitized version of the modern critical edition).[1] The manuscript is housed at The Rosenbach Library and Museum as MS 443/21. The author, Chastellain, was a prominent figure at the Burgundian court, serving dukes Phillip the Good and Charles the Bold with distinction. L’outré d’amour, written in 214 octosyllabic octets, is an example of a Roman à clef, a narrative describing actual events presented as a fictional account using altered names. This is a later name for the genre, but this type of work was popular in mid-fifteenth-century Franco-Burgundian culture, where a fractious political situation sometimes made the overt enunciation of one’s privately-held views problematic.

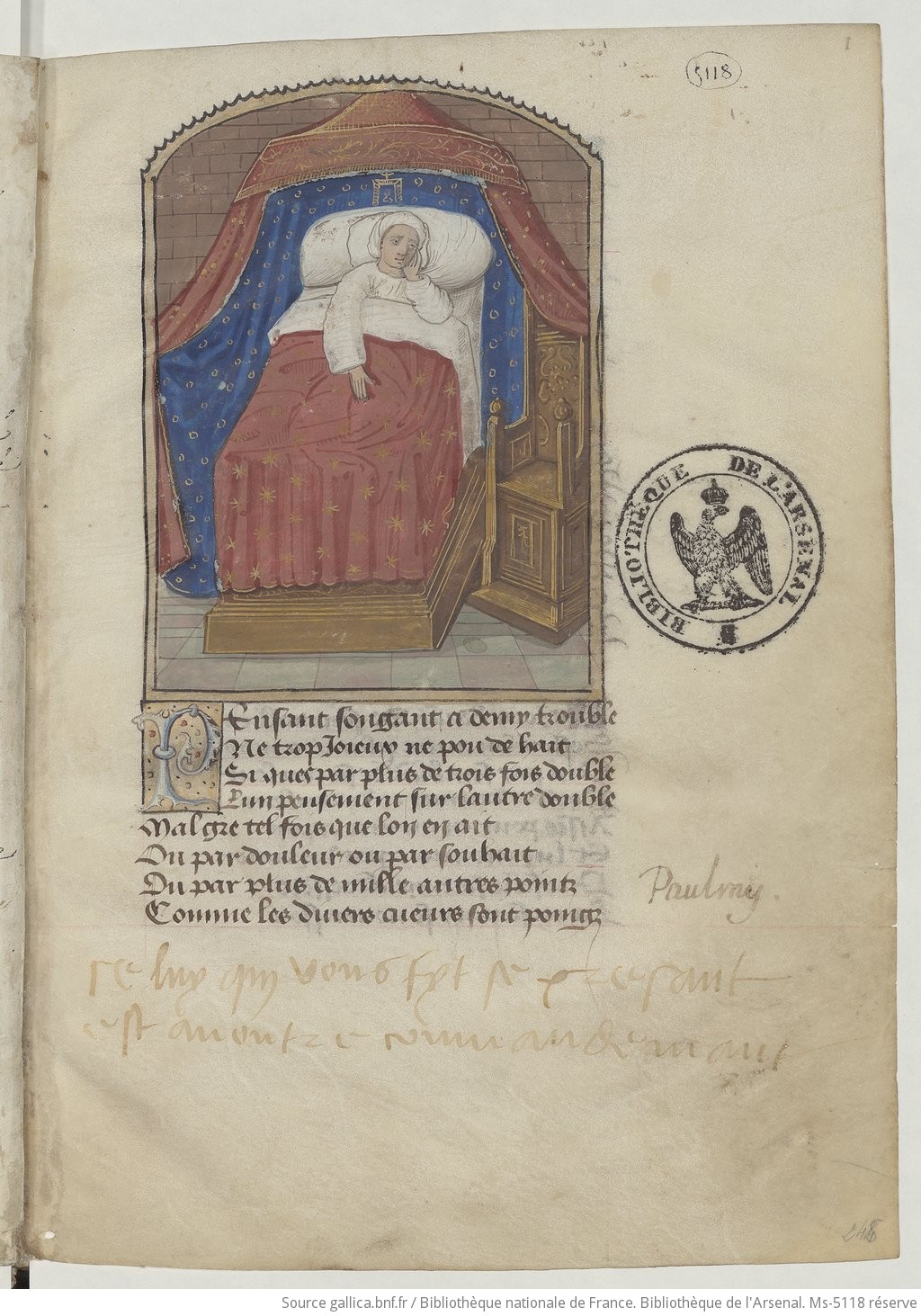

The Rosenbach manuscript, which is missing four stanzas between folios 7 and 8, was likely produced in Western France in the 1460s or 1470s, judging by the style of the bâtarde script and the four unframed miniatures (four more spaces for miniatures remain blank); it may well date from Chastellain’s lifetime. Ours is at least the seventh known manuscript copy of the text to be identified, and it can be added to the five exemplars listed in the Archives de littérature du moyen âge (none of which is currently fully digitized), and a copy at the Bibliothèque de l’Arsenal with eleven miniatures that has very recently been digitized. Chastellain’s text became quite popular in the early sixteenth century, as it was included in the earliest printed anthology of Middle French poetic texts, the Jardin de plaisance et fleur de rethoricque, first issued by the Parisian printer Antoine Vérard in 1502 and re-printed no fewer than eight times before 1528.

The Rosenbach Museum and Library, MS 443/21, fol. 1r and Georges Chastellain, L’Oultré d’amours pour amour morte, Paris, Bibliothèque de l’Arsenal, Ms 5118, fol. 1r (253 x 174 mm versus 203 x 143 mm in size)

Given the popularity of this text in Renaissance France, the manuscript in question is especially notable on account of its subsequent presence in an important library some fifty years after its creation, when it was well on its way to becoming a classic. The Rosenbach manuscript was in fact once owned by Jacques Thiboust (1492–1555), a noted humanist book collector in early-sixteenth-century France.[2] Thiboust trained as a jurist and remained deeply devoted to the region around his native Bourges, in the Berry. He served as a notary and secretary to King Francis I and his sister Marguerite de Valois in an illustrious career that brought him into contact with a wide range of poets and chroniclers. He is best known for being at the center of a literary circle of friends in Bourges in the 1520s, 30s, and 40s, which brought together local clerics, merchants, scholars, and physicians, but also such luminaries as statesman Guillaume Bochetel, the archbishop of Bourges Jacques Leroy, the poet and translator of classical texts François Habert, and the eminent poet Clément Marot. Thiboust’s renown was such that already at the age of 24 he was the subject of a portrait, currently untraced, by the leading French court artist of the time, Jean Clouet. A number of personal manuscripts in Thiboust’s own hand survive, recording his land holdings surrounding his manor at Quantilly, near Bourges (Bourges, Archives départementales du Cher, G 61 and E 108; Paris, BnF, MS fr. 32954). A fascinating Friendship Book or Liber amicorum that belonged to Thiboust (Paris, BnF, MS fr. 1667) contains numerous odes and poems to Thiboust’s many friends.

We know the precise details of Thiboust’s acquisition of the Rosenbach manuscript on account of an autograph inscription he wrote on the inside front cover, in a fine bâtarde script. It reads: “C’est au Seigneur de Quantilly M. Jacques Thiboust, notaire et secrétaire du Roy et esleu en Berry. Et le luy a donné sire Jehan Jaupitre son frère. En mars 1535.” (“This belongs to the lord of Quantilly Mr. Jacques Thiboust, notary and secretary to the King, and elected in Berry. And it was given to him by his brother Jean Jaupitre, in March 1535”). Jaupitre appears to have been Thiboust’s wife Jeanne de la Font’s half brother; the manuscript thus exemplifies the type of infra-familial gift of a book that was becoming so popular in Renaissance France. “Des livres de M. Jacques Thiboust” (“From the books of M. Jacques Thiboust”) is additionally written on lower pastedown, and the date of “mars 1535” is repeated on recto of first flyleaf. The title of the work, “Cy commance le livre de l’outré d’amour pour amour morte,” has also been added in upper margin of folio 1r. Like other books that belonged to Thiboust, this manuscript has his name all over it!

The Rosenbach Museum and Library, MS 443/21, upper pastedown, with inscription by Jacques Thiboust, and lower pastedown, with additional inscription

As if that weren’t definite evidence enough to establish ownership, the manuscript bears Thiboust’s unique, ink-stamped ownership mark on the verso of the front flyleaf and the verso of folio 37.[3] The bookstamp displays Thiboust’s arms. These are, in French heraldic terms: “écartelé au 1 et 4 d’argent à la face de sable, chargé de trois glands d’or accompagné de trois feuilles de chêne de sinople, deux en chef, une en pointe; au 2e d’argent à une anille de moulin de sable [Dumoulin] ; au 3e d’or à deux perroquets adossés de sinople [Rusticat]; et sur le tout d’azur à une étoile-comète d’or [Villemer]. Hand-painted variations of the arms occur in other books owned by Thiboust, including his Paris Liber Amicorum (Paris, BnF, MS fr. 1667) and a manuscript register now in the Bibliothèque municipale of Bourges (Ms 373, fol. 3v). Above and below the square armorial stamp are the mottoes, in Latin and French respectively, “Lex et Regio” and “Qui voit s’esbat,” which can be translated “Law and Region,” or “Law and Land;” and “He who sees frolicks, relaxes, or amuses oneself.”). The latter is in fact an anagram of Thiboust’s first and last names (switching I for J and a V for a U), devised by the noted poet Clément Marot.[4] For good measure, the French motto has been recopied in pen below the stamp on folio 37 verso, and signed, again, by Thiboust himself.

The Rosenbach Museum and Library, MS 443/21, flyleaf i verso and fol. 37v, showing the armorial bookstamp, motto, and signature of Jacques Thiboust

Thiboust’s serially reproducible woodcut ownership mark is the earliest of its kind to be used in France, though other, earlier examples survive from German-speaking regions. The stamp itself is interesting for its rather cutting-edge design: based on its curling, strapwork ornament, I would date it well into the 1520s, not 1518–1520 as Arthur Rau had assumed (see footnote 3). It is found in other fifteenth-century manuscripts Thiboust owned (for example a copy of Alain Chartier’s L’espérence ou consolation des trois vertus now in the Morgan Library & Museum), in contemporary printed books (a copy of Le couronnement du roi François [Paris, 1520] held at Yale University Library), and in significantly older items, including this twelfth-century version of Josephus’s Antiquities, now in the Bibliothèque nationale de France (ms. lat. 15427), which he gifted to his friend Bochetel. A particularly good example occurs in an example of the anonymous La voie d’enfer et de paradis, Les Enluminures, TM 775, where the stamp’s presence on the first page of this imperfect copy proves that it had already lost its first few leaves by the time it came into Thiboust’s hands (see the excellent Les Enluminures description and additional photos here).

La voie d’enfer et de paradis, Bourges, c. 1460. Les Enluminures, TM 775, verso of final flyleaf-fol. 1r, an example of another mid-fifteenth-century French manuscript with Jacques Thiboust’s bookstamp and inscription

A final—though conjectural—piece of evidence that might help localize our manuscript even more precisely within Thiboust’s ownership is its potential inclusion within a list of contents of Thiboust’s library found in his Liber Amicorum mentioned above (Paris, BnF, MS fr. 1667). On folio 156r of this album, within what seems to be a list of literary works from which Thiboust drew excerpts, appears (six lines up from the bottom) an entry that can be read as “Le couspré d’Amour,” (?) perhaps a misspelling of “Le l’oustré d’Amour”? The item above it is “La voye du Paradis,” which seems to be identifiable with the manuscript of La voie d’enfer et de paradis, mentioned and illustrated above (Les Enluminures, TM 775). The roman numerals in the right margin of the list, which are not continuous, are puzzling. Could these allude to the year in which Thiboust received the works, in which case the “XXXV” (35) for the mysterious “Le couspré d’Amour” would accord with the 1535 year recorded in the Philadelphia manuscript? Regardless of whether this link can be made definitely, the Philadelphia manuscript remains a previously unnoticed addition to Thiboust’s library, and further confirms this humanist bibliophile’s interest in the creation of a French literary canon through the collection of manuscript exemplars, even at a time when this text was widely available in print.

Paris, BnF, MS fr. 1667, fols. 155v-156r